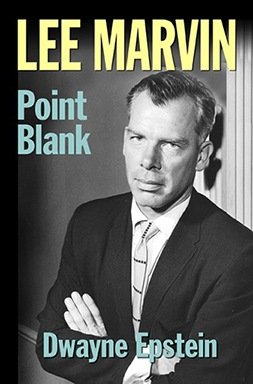

Lee Marvin: Point Blank Biography by Dwayne Epstein

- Posted: April 07, 2023

- Category: Writing 101

Image credit: Schaffner Press, 2013

The definitive portrait of iconic Hollywood legend Lee Marvin. Star of The Dirty Dozen, Cat Ballou, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Emperor of the North, Point Blank – and many others – “Lee Marvin: Point Blank,” is the first full-length, authoritative biography of this influential Hollywood star.

Need an essay about this biography? Team of professional writers at Academized.com is here to help you. They are experienced to handle any type of "write my essay for me" request with a guaranteed result. Get your essay written by expert.

Lee Marvin: Point Blank was the first full-length, authoritative and detailed story of the iconic actor’s life to go beyond the Hollywood scandal sheet reporting from earlier books, and provide an appreciation for the man and his acting career and the classic films he starred in, whether it was his chilling titular villain in “Who Shot Liberty Valance” or the paternal yet brutally realistic platoon leader in “The Big Red One.”

And, while Marvin was best known for his icy tough guy roles, veteran Hollywood writer Epstein provided readers with a portrait of a much deeper, more complex individual who took great risks in his acting and career, often joining forces with relative unknown directors of the time like John Boorman and Sam Fuller. Yet, although he was voted the leading male action star in 1967 and won an Academy Award (Cat Ballou), very little was known of his personal life, his family background, his experiences in WWII, his relationship with his father, family, friends, wives, and his ongoing battles with alcoholism, rage and depression, occasioned by his postwar PTSD.

After years of research, interviews with family members, friends, and colleagues, and complete with rare photographs and illustrative material, LEE MARVIN: Point Blank provided a full understanding and appreciation of this acting titan’s place in the Hollywood pantheon in spite of (or perhaps because of) his very real and human struggles. Moreover, this biography provided a penetrating psychological and sociological analysis of Lee Marvin and his role in shaping the image of the violent male in modern film.

By exploring Marvin’s family history and his formative years as well as the harrowing combat that Marvin was involved in the Pacific campaign in WWII, Epstein gave readers a portrait of a man shaped and shattered by violence, yet one who, having been intimately acquainted with it, could bring it home to the film audience with an intensity and realism previously unseen in modern cinema.

Articles:

- What Lee Marvin Really Thought of the Dirty Dozen

- Other Sources: James Garner on Lee Marvin

- Gregory Walcott Interview for His 87th Birthday!

- My Interview with the Late, Great Woody Strode

- Lee Marvin Passed On This Day In 1987

- Archive: My Interview With Samurai Widow, Judy Belushi